The First Of May, 1977 (2014)

deconstruction of a family 8mm film, slide / sound installation

2014

29-slides, two-channel sound installation, 13 min 20 sec EN, 12 min 16 sec SRB, 15 min 48 sec DE

The work The First of May, 1977 is a deconstruction of an 8mm family film in which a small act of violence is isolated and played out while its cause remains concealed.

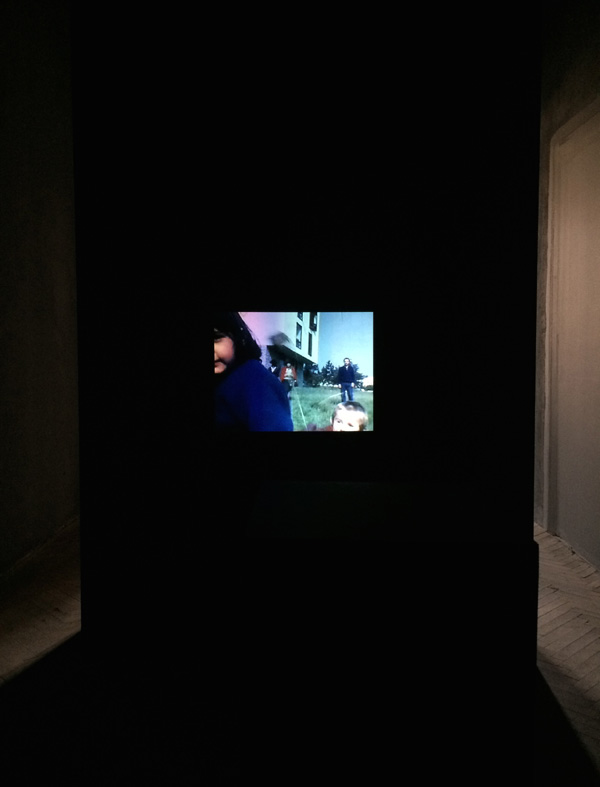

Split into two separate locations, the work is comprised of a sound piece in one space which is based on interviews with members from the two families who witnessed and directly participated in the act of violence and a slide projection made from the 8mm film in the other.

Considering the event occurred in 1977, it now exists as a distant memory for each person interviewed and the differences and discrepancies in their accounts attesting to the subjective nature of memory and perception.

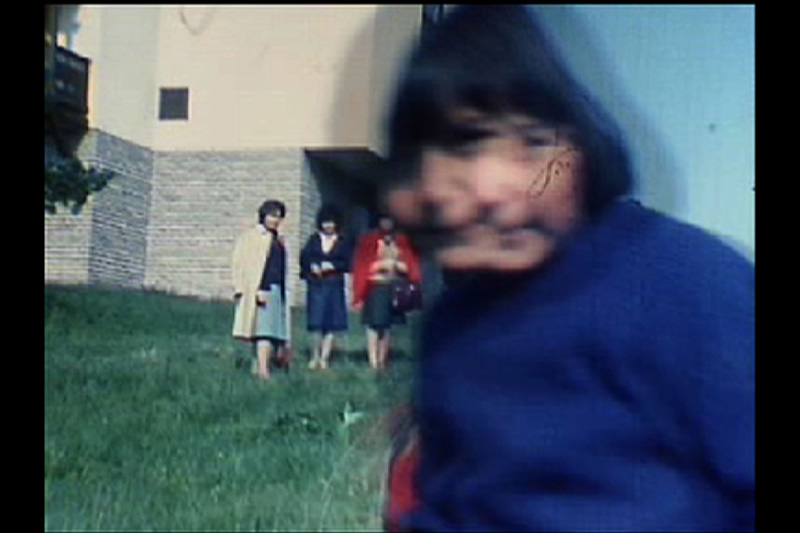

Originally captured in a single moment, the act of the boy throwing a rock at the girl’s head becomes 29 slides which are then looped into a four-minute sequence. By creating stills from the 8mm family film and representing only a brief instance from the day it occurred, the slide projection isolates and prolongs the act of violence.

By separating the testimonials of the witnesses and participants (sound) with the “evidence” of the act of violence (slides), the visitor engages in the act of becoming a witness themselves by carrying the contents of one space mentally to the other or at least a thin remembrance of it. Because the two spaces are approximately identical in character and the distance between them is just long enough to begin the process of forgetting, the absence of the images and presence of sound in one space and the absence of the sound and presence of the images in the other space creates a parallel scenario to the act which is itself in question.

Here you can hear the sound installation in English:

Here you can hear the sound installation in Serbian:

Here you can hear the sound installation in German:

The Girl’s Sister Remembers:

The girl’s sister doesn’t remember anymore. She doesn’t remember who was there. She says there were eight of them, although, she doesn’t remember if their grandmother was also there. She can’t recall it, but says she thinks she was, since their grandmother used to go everywhere together with them. What she knows for sure is that four of the children were with their parents. But she is really not able to invoke it at the mo- ment, either in her memory or visually. She re- members the event itself, that she and her family had a picnic and that it was okay; they were play- ing, running and jumping around. She says that the only thing that comes to mind is that the boy and the girl were teasing each other and fighting. She says she doesn’t know anymore what else the boy and the girl were doing, or if she was near them. The only thing she remembers is the mo- ment when the boy screamed. She remembers that everyone started shouting and running to- wards the boy. She didn’t see what was going on, and can’t remember if a stone or something flew towards the boy. She doesn’t remember if she actually saw it or if it’s what she was told by oth- ers. She doesn’t remember when it was or how old they were. She remembers it was unpleasant and that’s all. As far as she remembers the story was that the girl hit the boy and that the girl had probably picked up a stone from somewhere, the grass maybe.

She thinks the family was on a grassy hill and doesn’t remember how the stone had gotten there. She says she remembers the story that the family told her better than what she experienced. She says she is 44 years old now and thinks that it wasn’t winter time, the weather was nicer and it was spring or summer. She doesn’t know what year it was, whether it was 1979, 1975, or 1976 but that it wasn’t 1980.

written excerpt from the two-channel sound installation

The Boy’s Brother Remembers:

There was the boy and girl’s grandmother. There was the girl’s father, mother, sister and the girl herself. There was the boy’s mother, father, the boy’s brother and the boy himself. The boy’s brother remembers that they parked on the mountain Divčibare and that he and the girl’s sis- ter played with a ball. He thinks shortly and says he can- not actually remember anything except what he had seen in the film after the fact. He says the boy and his mother, their grandmother as well as the girl’s mother and father were chat- ting. He and the girl’s sister were playing with a ball, while the boy and the girl were hopping around, running, jumping, and pushing each other. And then, he says the girl pushed the boy from be- hind. The boy fell down and the girl ran away. The boy then grabbed a stone and threw it at her head. Then nothing, the camera fell in the grass. He can’t really remember how long it lasted but thinks about half a minute, not longer. He doesn’t remember what happened after. He says he might remember more if he hadn’t seen the film twenty times.

written excerpt from the two-channel sound installation

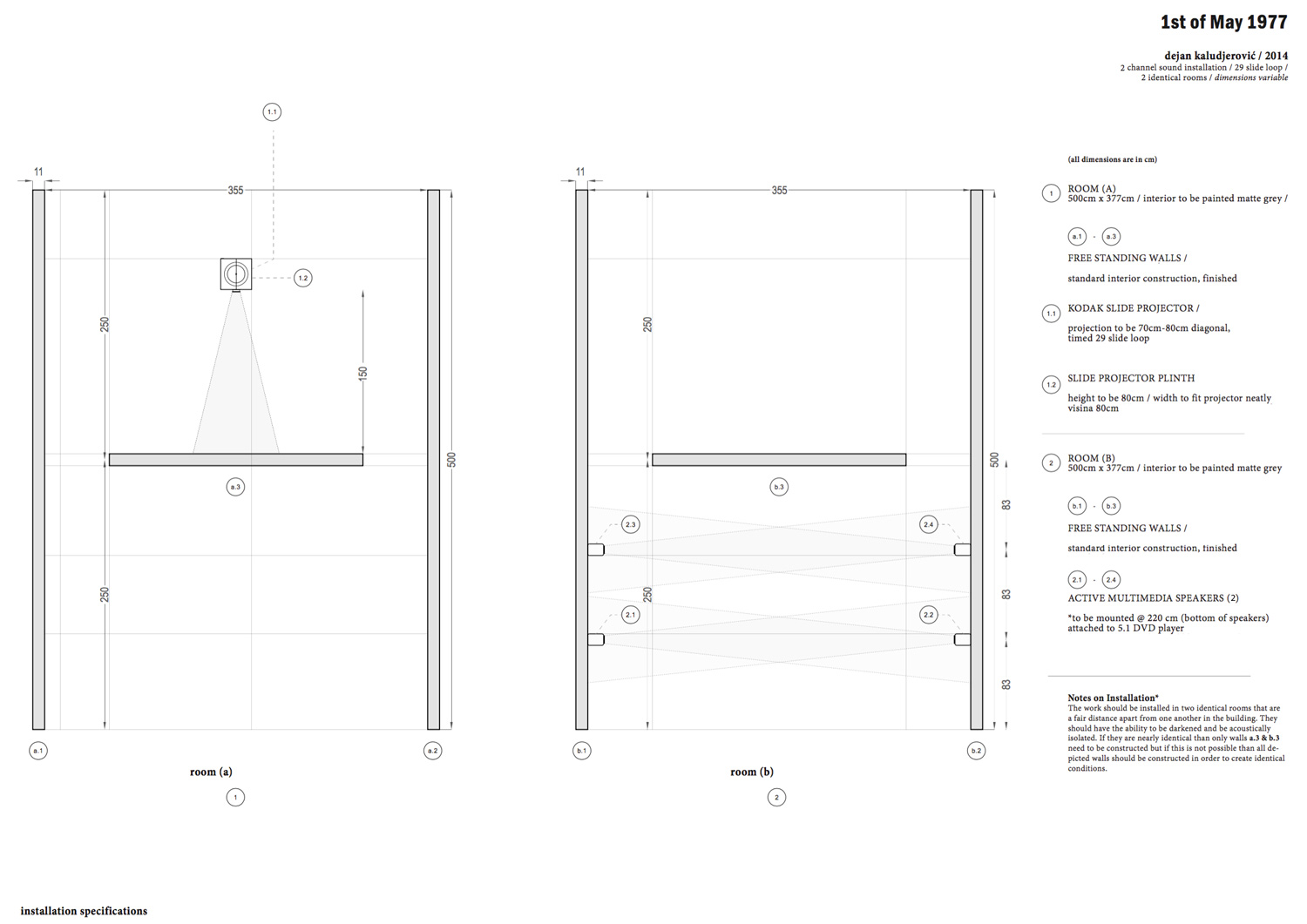

plan of the set up

In 2014, the artist produced a sound and slide installation called The First of May, 1977. This work was shown at the 55th October Salon in Belgrade, and later, in 2015, at the Salzburger Kunstverein as part of the touring exhibition Invisible Violence. Two identical, narrow rooms are constructed in a larger gallery space. These rooms are neither adjacent nor near one another; rather, they are deliberately removed from one another. Other installations and rooms separate them. It is as if they are meant to be accidentally identical in their individual discovery by attending viewers. There is a deliberate gap between these two spaces, like a gap in belief, or indeed, like a gap in memory – a kind of déjà vu. There is also certainly the sense of time being displaced, or even a Nietzschean return of time, when the second installation is discovered. Each room is painted black and has a self-standing wall placed within it, dividing the room into two. One room has several, dissonant voices speaking within it, one after the other, as if each voice is that of a person somnambulistically responding to an unknown question. The artist has assembled their replies to his single question into a narrative. We hear responses from the mothers of two children, a boy and a girl, then from their fathers. The boy then responds, while the girl refuses to remember the situation.

This first room has descriptions of these various interlocutors of an event that apparently happened on the eponymous date. The other black room simply has a series of diapositive slides projected, one by one, onto its central wall. The second room seems to depict this described moment, which appears to be something rather innocuous actually, and clearly from a somewhat distant childhood. We see only blurry, colour projections of a long-ago event with children in a garden, concluding with close-ups of, presumably, the boy in question.

The title immediately creates associations with uprising and revolution, the passing of states from one political body to another, labour rights, and naturally, the anthem “The Internationale”. The First of May is, after all, International Worker’s Day. As such, it is a holiday, a global one, and historically relevant (if not internationally celebrated) as such. The title may, however, only be indexical and thus coincidentally meaningful. The entire artwork arrives out of the artist’s own probing of the complexity of memory, truth and the ongoing, often severe manipulation of narratives in the context of the Yugoslavian wars in the 1990s. And here, colliding with a troubled history of war and tragedy (and related concurrent and postwar narratives) – and perhaps also entwined with occasions that problematically mark modernism’s development (the influence of Marxism on society and political structures) – here, appears some documentary evidence of, it seems, a naïve act of violence committed by a child.

The artist is indeed very close to the subject of the artwork. For here, we are hearing his family members describe the moment when he, the boy who also speaks in the sound installation, himself struck his cousin with a stone many years ago, and here we see photographic remnants presented as some form of self-incriminating evidence. The artist himself dissects and analyses this long-ago moment and its documentation and its later, flawed descriptions to engulf it within the dream-like, playhouse mirror structure of its own open fragmentation. Its visual presentation and adjoining subjective verbal descriptions are based on several mnemonically challenged narratives as they interact with each other and become contaminated by associations of war and its representations.

The artist here stages and re-stages the event like in a feverish dream endlessly caught in a dark labyrinth, or indeed, as we might imagine a detective obsessively reviews the evidence of a crime. In this case, it is the act of a child who, at the age of five, we presume, has not developed his conscience or sense of the world enough in order to always differentiate right from wrong. Yet, the staging of this everyday event by the artist is not intended as some sort of confessional self-portrait. It, in part, appears to underline his need to strip layers of normalcy as it is made up in shared narratives down to a kind of speculation in visual form of darker regions of consciousness, identity-development and the production of the ego. These forms themselves flicker in and out of the structures of shared language and story-telling, for example, as they are inevitably caught up in webs of ideology and the collective wish fulfillment that ensures collective belief.

Dejan Kaludjerović is interested in the everyday inscriptions of power, culture, language, belief and law on the body and on the mind. His work, he says, is “mainly concerned with issues of responsibility and manipulation.” He thus examines the usual suspects, such as forms of mass media, education systems and indeed the influence of family and society on the psyche. But underneath this ongoing examination, as we have seen, we can pinpoint (and the artist openly admits to) a central concern with violence, and the nitty-gritty that emerges from mechanisms of power and capitalism as they are inscribed on the body and mind. Thus, when we unpack a work such as The First of May, 1977, elements of a long- ago act unfold into some sort of presentation of documents and fragments to be examined, and the testimonies then bear witness to something not only within the room, but outside of it, in the streets around the gallery space, and in living histories. We can ascertain several unfolding situations in this work. Matters of innocence and non-innocence, the passage into adulthood and all that carries with it in terms of borne memory, the production of perception, the role of day-to-day cultural propaganda, even matters of political crises and war – these all begin to emerge as we see a kind of sketch of the human condition as it is emerging and shifting in the malleable shape of a child and the memories attributed to a long-ago act, here caught up in a web of associations around the war in Yugoslavia.

excerpt from the text Repositories of Unseen Impulses: A Few Notes on the Work of Dejan Kaludjerović by Séamus Kealy